NIGERIA, indeed, has come a long way, 57 years into nationhood. However, whether or not its speed and height of development are commensurate with that age is subject to debate.

While it cannot be said that nothing has been achieved throughout those stormy years, there seems to be a preponderance of the belief that the country has underperformed in most of the major indices of nationhood.

In the education sector, for instance, many people today find it almost unthinkable that a 57-year-old country, which had the rare privilege of having its first university even more than a decade before its independence, only last year managed to have one of its 152 universities rated among the top 1000 in the world.

Fifty-Seven years after independence, despite having produced a Nobel laureate and despite the generally accepted centrality of quality education to social, scientific and technological advancement of nations, Nigeria still remains a country where the entire public university system can be shut down, sometimes for nearly a year!

Indeed, there is a sense in which it appears as if successive administrations in Nigeria, and the political class, do not place the expected value on education.

Nigeria today is still plagued with unimaginable levels of students’ overpopulation at the basic and secondary school levels, decrepit infrastructure at all levels of education, lack of quality supervision in schools, and generally low output of quality researches in its university system due to a cocktail of factors, chief among which is inadequate funding.

Despite its oil wealth which it could have deployed to facilitate the provision of qualitative education infrastructure, Nigeria still holds the record of the country with the highest number of out-of-school children in the world.

Every year, consistently, Nigeria absorbs less than 30 per cent of candidates applying for tertiary education. There is alleged massive corruption in the system, and a general (almost palpable) low morale among teachers and other public institutions’ staff.

Not Yet Uhuru

Reviewing the progress so far made by the country in the sector in its 57 years of existence, the Director, University of Ibadan Distance Learning Centre, Professor Oyesoji Aremu, is unsparing in his assessment.

On the scale of 10, Professor Oyesoji scores Nigeria 3.

According to him, the extent of progress made in the education sector invariably determines the extent of development and growth a nation achieves.

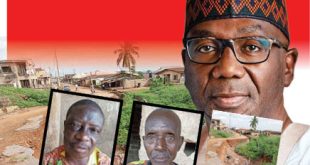

Education: The high and low of quest for excellence

Is this really school?

“Show me a country with a robust and well funded-education industry, I will point to you a country that will be the envy of others in all-round and complete development.

“Putting the nation’s achievements in education on a scale of 10, and comparing her with her contemporaries who had independence about the same period, I will, conservatively, grade her 3.

“Mainly, the education industry has three major sub-sectors: early childhood and primary, secondary and tertiary. My take in this intervention is the secondary sub-sector, given its importance as a feeding unit to tertiary education.

“Obviously, the pre-primary and primary education has suffered a terrible neglect for a long time; but the kind of fate that has befallen the secondary sub-sector, especially from the mid-80s, is colossal.

“Like the primary sub-sector, it has also suffered a total abandonment with only occasional leap commitment on the part of the state governments. There is a continued low enrolment figure in secondary education in Nigeria with many out-of-school children.

“The reasons for this are multifaceted. They include, among other things, poverty, ignorance on the part of parents and guardians, inconsistent policy and occasional policy somersault on the part of government (examples abound in some states), unmotivated teachers, and decay in facilities.

“Unfortunately too, annual release of the West African Examination Council and NECO’s results has shown that, of recent, national average performance is on the decline in many states. This becomes worrisome given the fact that the tertiary sub-sector would be accessed by not-too-good candidates. Consequently, the tertiary sub sector is left to battle to salvage. More often, the trend there (tertiary sub sector) is also very disturbing.”

He is not alone on this view. The deputy vice chancellor (Academics), Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Professor Catherine Eromosele, lamented that there has been a reduction in quality.

“Before the 1990s, products of Nigerian university fitted well and even excelled in universities in Europe and America. The lecturers were dedicated and enjoyed generous grants from government to pursue research.

“However, dwindling funds and proliferation of universities have compromised the standards in education in recent times,” she says.

Professor of Mass Communications and Media Studies and vice chancellor, Adeleke University, Ede, Osun State, Professor Ekundayo Alao, on his part believes some measure of achievement has been recorded, especially in the education standard, which he describes as “enviable – at least within the (African) region.”

For instance, he says, no other country in the (African) region, except South Africa, has the number of universities Nigeria parades.

But that is where it ends. Professor Alao lists a number of factors that have consistently beset Nigeria’s education development, beginning with lack of coordination and continuity.

“The real problem we have is that we are not coordinated. From one government to the other, there is no sequence of thoughts, of planning and continuation of ideas. (With) every government, from the civilians in the 60s, the military (governments) of the 70s and some part of the 80s, and even the civilians now, there is no coordination.

“There needs to be continuity in education. Programmes laid down by the (previous) governments should be adequately followed. There is no sequence,” he stressed.

He also questions the relevance of the curriculum to national needs.

“Our syllabus needs to be reexamined in the area of national building. You don’t just put a syllabus together (especially at the tertiary level) that is not directed to national development. There are so many degrees that are being awarded that have nothing to do with development.

“For instance, History should (be taught to) every student, right from the primary school to the tertiary institution. When you don’t know even the history of your country, you have lost all, he noted.

Professor Alao also faults Nigeria’s handling of the geese that lay the golden eggs: teachers

“The way we handle our teachers (in the primary, secondary and tertiary institutions) needs to change. I think the nation needs to address the role of these professionals. Teachers, by their calling, are the people that build the nation. There is no nation that has grown to a very reasonable height today that has not developed its own teaching professionals. But in Nigeria, we neglect our teachers.

“When government makes promises, I strongly believe that government should follow up those promises and fulfill them.

“Right now, ASUU has taken a break; but they will go back to their strike. Very soon, teachers in the polytechnic will take the cue, and those in the colleges of education will follow.

“Imagine a university that has been closed down for one and a half years, and nobody is bothered – even the federal government is not bothered! Things like these hinder our educational growth.”

Not all bad news

But these notwithstanding, Emeritus Professor of History of Education at the University of Ibadan, and immediate past ambassador and permanent delegate of Nigeria to UNESCO, Michael Omolewa, believes there are still many reasons to celebrate what he calls the “advancement in the education sector.”

“Before the attainment of self-government, and later independence, Nigerians could not make decisions with respect to its education policy or programmes. But today Nigeria decides what it wants and what it does not want in the educational system, practices, planning and management.

“In the process, mistakes have been made, but that in itself is a mark of development, as the people learn from mistakes.

“In the past, Nigeria was represented at the international organisations by the British government. At the international stage, gone are the days when Nigeria did not have a voice at the institutions and agencies set up for the promotion of education.

“Nigeria has produced the secretary-general of the commonwealth in the UK, the president of the general conference of UNESCO in Paris, France and the chairman of the International Conference on Education in Geneva, Switzerland.

“Nigeria has been active in the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals and the succeeding Sustainable Development Goals. Nigeria is no longer passive in the discourse of global planning and management of education practices and philosophy.”

He also lists as achievement the “considerable expansion” in the number of universities from the only two universities in the country (at independence) with only a few graduates, to over 140 universities.

“This means that access to education has increased and there is an increase in opportunities to learn. Enrolment has also increased at all levels of education, primary, secondary and tertiary. Nursery education and pre-primary education has expanded exponentially,” he says.

Another major gain over the years, according to Omolewa, is the introduction of the Universal Primary Education and its replacement by the Universal Basic Education (UBE), which he says has met the minimum standard prescribed by the United Nations Millennium Development Goals.

According to him, “Retention rates have also improved as several incentives, including free feeding, have tended to keep and sustain learners in the school.

“At the policy level, the country has witnessed the adoption in 1977 of the National Policy on Education, revised as required over the years. This document is like the education constitution which spells out the duties and responsibilities of government, and the expectations from the people.

“The policy encourages the use of local languages and the establishment of centres and Institutes of African Studies – things that were unthinkable during the colonial period.

“The country must celebrate advancement in adult learning and the promotion of literacy. The university of Ibadan became the first University in Africa to win the coveted UNESCO Literacy Prize in 1989. Kano agency for Mass Education won the Honourable Mention for the same UNESCO Literacy Prize in 1980. There has been an increase in the literacy rate in the country that should make the nation rejoice.”

However, Omolewa agrees there are challenges such as “Funding for education which he said is lamentably inadequate adding that students’ performance is not encouraging in most parts and the use of the modern technology is still absent in many schools spread across the nation; the teaching profession has become increasingly less attractive.

“There is also still a major gap in the provision of education across regions, religious groups and age groups, and between the rural and urban centres. For example there are concerns about the poor performance of Nigerian students in the West African Examinations Council examinations.

“The Global Competitiveness Report published in 2012/2013 ranked Nigeria 102nd out of 144 countries in the aspect of the quality of primary education; 140th out of 144 in primary education enrolment; 120th in secondary education enrolment, and 111th in tertiary education enrolment.

“There are concerns that the quality of education may have fallen as many products of schooling remain incapable of expressing themselves in articulate English or demonstrate competence in computing figures. There are still inadequate spaces for students who are qualified for admission to universities and other higher education institutions, and there is unemployment of graduates. But these challenges are by no means insurmountable.”

He lists efforts being made to address many of the problems. For example, he says, institutions are being encouraged to develop skills for their learners at all levels to make them jobs creators rather than job seekers.

More private institutions are being founded to complement the contribution of government.

In the words of Professor Eromosele, “students of technical and vocational colleges represent creative and innovative minds capable of bringing technological changes to the society and creating jobs.

“Our government needs to consistently fund that sector and motivate their teachers.”

(Tribune)

National Telescope national telescope newspaper

National Telescope national telescope newspaper